|

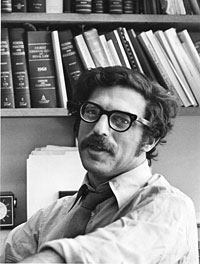

Michael Meltsner

news & recent activity | biography | interview | praise | contact | gallery Interview from Northeastern Law Magazine

A: Winning Furman v. Georgia was a shock. Before LDF's anti-capital punishment campaign, there had been no successful court challenge of the death penalty — even when it had been handed down in a blatantly racist or totally arbitrary manner. Despite a five-year court-imposed moratorium on executions, almost all observers predicted the Supreme Court would decisively reject our challenge. When the Court later bowed to public opinion and reversed direction, it still left us with a regulated death penalty where an unregulated one had been before. For better or worse, capital punishment is now a major legal and political issue and, given the incompetence with which death cases have been handled, I believe it will eventually wither away. As to Furman, whatever its shelf life, it saved 650 lives. Q: In your book, you write, "Many of my cases have been overruled or disregarded by later courts, brushed aside as if they never were; yet others have been woven tightly into the fabric of the law." Which of the cases "woven" into law stand out in your mind? A: I had many anti-segregation and race discrimination cases in mind when I wrote that. To name just a few, there is Turner v. Fouche, ruling there could be no economic test required for school board members; the Cypress case, in which the Fourth Circuit stepped in to force Southern hospitals to accept African-American doctors on their medical staffs; and a series of cases that ultimately led the Supreme Court to rule the death penalty for rape unconstitutional in 1977. Q: You worked alongside some of the most famous and influential civil rights leaders of the 20th century: Thurgood Marshall, William Kuntsler and Derrick Bell, to name just three. How did they, and the experiences you shared, shape your career? A: Thurgood Marshall could pack a law school course into an anecdote, but I remember most his stories about foibles of the Southern black lawyers I would spend a decade with. I never worked closely with Kuntsler but our few collaborations led me to admire his ability to attract media attention and brilliant colleagues like Arthur Kinoy. Derrick Bell takes nothing for granted; his passion for justice is infectious. I have always felt that I attended two law schools — one the Yale of great constitutionalist Alex Bickel, the other LDF with lawyer-teachers like Jim Nabrit, Jack Greenberg, Leroy Clark and Anthony Amsterdam. Q: What is your advice for today's civil rights lawyers? A: Given the politics of the day, and a seemingly intractable set of complex economic and social justice issues, public interest lawyers of all sorts face even more difficult challenges than we confronted in the civil rights era. They need to consider a wide range of tactics, including ways to facilitate direct action on the local level and to engage effectively in the legislative process. Developing class-based litigation models has long been a goal, but it's hard to imagine today's judiciary playing an assertive role in bringing about change. Still, worldviews change when crisis strikes, and one thing we know about the world we live in is that crises are inevitable. Civil rights lawyers need to be ready to act when the climate changes.

news & recent activity | biography | interview | praise | contact | gallery copyright © 2006-2010 Michael Meltsner |